청색광 성분이 풍부한 아침 조명과 제한된 저녁 조명의 복합 사용이 수면의 질에 미치는 영향

Effect of the Combined Use of Morning Blue-Enriched Lighting and Night Blue-Suppressed Lighting (MENS) on Sleep Quality

Article information

Trans Abstract

Objectives

Previous studies have shown that exposure to blue-enriched light in the morning or blue-suppressed light in the evening may positively affect sleep. In this study, we aimed to investigate the effect of combination of morning blue-enriched and night blue-suppressed lighting (MENS) on sleep quality.

Methods

Thirty workers were recruited. After one-week baseline evaluation, the participants were randomly assigned to either an experimental or a control group. Both were exposed to light in the morning and evening for two weeks. The experimental group used a lighting device emitting 480-nm wavelength maximized light in the morning and minimized light in the evening, while the control group used 450-nm wavelength light in the same way. The final evaluation was conducted using questionnaires and sleep diaries.

Results

Both groups showed statistically significant improvements in seven out of nine sleep quality measures (p<0.05). The experimental group showed improvement in sleep latency and sleep fragmentation compared to that in the control group (p=0.017). The control group showed improvement in wake after sleep onset. The ratio of participants who showed improvement and transitioned from abnormal to normal values was significantly higher in the experimental group for sleep latency (p=0.046) and in the control group for fatigue (p=0.012).

Conclusions

The findings suggest that the use of MENS significantly improves sleep quality. Although the difference in the improvement effect between different wavelengths of blue light was not substantial, the use of 480-nm blue light appears to be effective in reducing sleep latency.

서 론

성인의 10%-15%가 불면증을 호소할 정도로 만성적인 수면부족이 현대인에게 만연해 있으며 이는 빛에 부적절하게 노출되는 생활환경과 관련이 있다[1-4]. 특히 수면 전 스마트기기를 과도하게 사용하는 습관이나 아침 햇빛에 충분히 노출되지 못하는 환경은 수면의 질을 떨어뜨리는 주요 요인 중 하나로 작용한다[5].

망막의 내인성 감광성 망막 신경절세포(intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cell)는 시상하부 시교차상핵(suprachiasmatic nucleus)을 통해, 멜라토닌을 분비하는 송과선(pineal gland)과 연결되어 있다[6,7]. 내인성 감광성 망막 신경절세포가 빛에 의해 자극되면 시교차상핵으로 신호가 전달되어 시간의 변화가 감지되고, 이에 따라 생체시계는 주변 환경의 시계에 맞춰지게 된다[8-10]. 송과선은 주변이 어두울 때 멜라토닌을 합성하여 분비하는데, 이는 빛에 의해 억제되며, 특히 내인성 감광성 망막 신경절세포가 가장 민감하게 반응하는 청색 파장대의 빛 자극에 의해 멜라토닌 분비가 가장 극적으로 억제된다[11-16]. 아침에 청색광에 노출되면 일주기리듬의 동기화가 일어나 야간 수면위상이 전진되고 수면잠복기가 감소할 수 있다[17]. 그러나 야간에 청색광에 노출되면 멜라토닌 분비가 억제되어 수면잠복기가 증가하고 일주기리듬이 지연될 수 있다[18-21].

이러한 연구 결과를 토대로 아침에 청색광에 노출되거나, 야간에 청색광에 노출되지 않는 것이 수면에 어떤 영향을 미치는지를 밝히기 위한 다수의 연구들이 수행되어 왔다. He 등[22]은 1주 동안 아침에 1시간 30분씩 밝은 빛에 노출될 경우 수면잠복기와 수면분절이 감소한다고 하였고, Lack 등[23]은 아침 기상 전 1시간씩 밝은 빛에 노출될 경우 수면위상이 전진된다고 하였다. Raikes 등[15]은 6주 동안 아침 기상 후 30분씩 청색광을 조사하면 주간졸림증이 개선된다고 하였고, Li 등[16]은 2주 동안 아침 기상 후 1시간씩 청색광을 조사하면 수면위상이 전진되고 수면의 질이 개선된다고 하였다. Chang 등[24]은 5일 동안 취침 전 4시간씩 전자책을 보게 하면 야간 각성이 증가하고 수면잠복기 및 수면위상이 지연된다고 하였으며, Kayumov 등[25]은 청색광 차단 고글 착용 후 취침하게 하면 타액 멜라토닌 농도가 희미한 불빛 조건에서의 멜라토닌 농도와 유사한 수준으로 확인된다고 하였다. Knufinke 등[26]은 아침 기상 후 30분씩 청색광을 조사하고 취침 3시간 전부터 청색광 노출을 차단하면 수면잠복기가 감소한다고 보고하였다.

이렇게, 아침 혹은 야간에만 빛 중재를 시도하여 수면에 미치는 영향을 분석한 연구들에서는 수면의 질을 평가하는 여러 항목 중 일부만의 개선을 보고하고 있다. 아침과 야간에 복합적으로 빛을 조사한 연구는 매우 드물었고, 이에 우리는 이러한 복합 조사가 수면의 질을 개선시킬 수 있을 것이라는 가설을 세웠으며, 이를 확인하기 위해 아침 기상 후 청색광이 강화된 빛을, 야간 취침 전 청색광이 억제된 빛을 조사하여 수면의 질과 연관된 다양한 항목들을 평가하였다.

방 법

연구 대상

이전 유사 연구를 참고하여, 연구 대상자의 표본수를 효과 크기 1.0461, 유의수준 0.05, 검정력 0.80으로 계산한 결과 최소 26명의 대상자가 필요한 것으로 확인되어 중도탈락을 고려해 총 30명의 연구 대상자를 모집하였다[16]. 연구 대상자 선정 기준은 1) 30-49세의 남녀, 2) 스스로 수면의 질이 낮다고 느끼며, 3) 오전 6-9시에 기상하여 출근 시간이 일정한 직장인으로, 4) 신경계질환, 수면질환, 정신질환이 없는 자로 하였다. 제외기준은 1) 최근 1개월 이내에 수면제를 복용한 자, 2) 완전 맹시인 자, 3) 교대근무나 야간근무를 하는 자로 하였다. 이 연구는 서울대학교병원 임상연구심의위원회(IRB, 2204-078-1316)의 승인을 받은 단일 기관 연구로, 각 연구참가자에게는 서면 동의서를 받았다. 연구참가자는 서울대학교병원 임상시험 지원자 모집 사이트에 모집공고를 게시하여 모집하였고, 2022년 6월 10일부터 30일까지 21일 동안 모집하였다.

실험 절차

모든 연구참가자에게 첫 방문 시 수면 관련 설문평가를 시행하였고, 향후 수면일기를 기록할 수 있는 수면일기앱(LUPLE Inc., Seoul, Korea)을 핸드폰에 설치하게 한 다음 사용법을 안내하였다. 수면일기앱의 입력 화면과, 입력 자료를 토대로 출력한 수면일기 자료의 예를 Supplementary Fig. 1 (in the online-only Data Supplement)과 Fig. 1에 각각 제시하였다. 그리고 조용하고 안락한 환경에서 취침하고, 밤에 과격한 운동은 삼가며, 취침 전 텔레비전이나 스마트폰 등의 전자기기는 사용하지 않도록 교육하였다. 일주일 후 추적방문을 하게 하여 이전 일주일 동안 기록한 수면일기 자료를 확인한 다음, 무작위 배정을 통해 연구참가자를 15명씩 실험군과 대조군으로 나누었다. 실험군과 대조군에게 외관은 동일하나 발산광의 색온도가 다른 조명기기(LUPLE Inc., Seoul, Korea)를 제공하였고, 이후 2주 동안 아침기상 후 30분, 야간취침 전 30분씩 조명기기의 빛을 받게 하였다. 조명기기는 참가자로부터 50-100 cm 사이 거리에, 안면부를 향하여 두게 하였고, 조명을 받으며 일상생활을 하도록 하였다. 총 2주 동안 조명기기를 사용하면서 수면일기앱으로 수면일기를 기록하게 하였고, 2주가 경과한 후, 최종 방문을 하게 하여 처음 시행했던 것과 동일한 설문평가를 다시 시행했다(Table 1).

An illustration of sleep diary record written with sleep diary application. Blue rectangle containing dots inside, morning light exposure time; Brown rectangle containing dots inside, night light exposure time; White rectangle located between the gray bars, wake time after sleep onset; Gray bar, sleep time; Green rectangle, time actually falling asleep; Black outlined rectangle with any background color, time lying in bed; Purple rectangle, time getting out of bed.

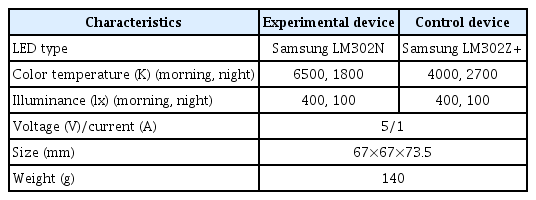

조명기기

실험군과 대조군에게 지급된 조명기기는 동일한 모양과 색으로 구성된 외장을 갖추었으며, 크기나 무게 등의 제원은 동일하였다(Table 2). 실험군에 지급된 조명기기는 아침에 480 nm 파장의 청색광이 최대화된 빛(색온도 6,500 K)을 발산하고, 밤에 480 nm 청색광이 최소화된 빛(색온도 1,800 K)을 발산하도록 설계되었다. 반면 대조군에게 지급된 조명기기는 아침에 450 nm 청색광이 최대화된 빛(색온도 4,000 K)을 발산하고, 밤에 450 nm 청색광이 최소화된 빛(색온도 2,700 K)을 발산하도록 설계되었다(Fig. 2). 450 nm의 빛도 청색광에 속하지만 내인성 감광성 망막 신경절세포는 480 nm 부근의 빛에 가장 민감하게 반응한다는 기존 보고를 감안하여, 이 파장대를 약간 벗어난 청색광 영역의 빛을 사용했을 때의 효과를 실험군의 효과와 비교하고자 하였다[13,14].

Wavelength characteristics of emitted light from the two different lighting devices. A: Experimental device emits morning light (blue line) with 480 nm wavelength maximized and night light (brown line) with 480 nm wavelength minimized. B: Control device emits morning light with 450 nm wavelength maximized and night light with 450 nm wavelength minimized.

평가 항목

참가자들에게 시행한 수면관련 설문평가 항목은 다음과 같다. 1) 수면의 질: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)을 이용하여 평가하였고 6점 미만을 정상 범위로 삼았다[27]. 2) 불면증: Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)로 평가하였고, 8점 미만을 정상 범위로 보았다[28]. 3) 주간졸림증: Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)을 이용하여 평가하였고, 11점 미만을 정상 범위로 판단하였다[29]. 4) 피로도: Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS)를 이용하여 평가하였고, 총점 기준 37점 미만을 정상 범위로 보았다[30]. 5) 우울증: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)을 이용하여 평가하였고, 10점 미만을 정상 범위로 해석하였다[31].

참가자가 수면일기앱으로 기록한 수면일기 자료로 다음 항목들을 확인하였다. 1) 수면잠복기(sleep latency, SL): 연구참가자가 불을 끈 이후부터 잠들 때까지 걸린 시간으로, 20분 이하일 때를 정상 수준으로 간주하였다. 2) 수면효율(sleep efficiency, SE): 침대에서 보낸 시간 대비 총 수면시간의 백분율로, 85% 이상인 경우를 정상 범위로 보았다. 3) 수면 시작 후 각성 시간(wake after sleep onset, WASO): 수면 시작 후 최종 아침 기상 전까지 중간에 깬 시간의 합으로, 30분 이하일 때를 정상으로 생각하였다. 4) 수면 중 각성 횟수(Number of awakening): 수면 시작 후 최종 기상 전까지 깬 횟수의 합으로, 0회에 가까울수록 양호한 수면으로 보았으며 정상과 비정상을 구분하는 값은 설정하지 않았다. 이와 함께 총 수면시간, 잠에서 깬 후 침대에서 벗어나기까지 소요시간, 주관적 수면의 질을 평가하였다. 주관적 수면의 질은 대상자가 아침 기상 후 지난 밤의 수면 상태를 주관적으로 평가하여 ‘아주 나쁨(1점)’부터 ‘아주 좋음(5점)’까지의 다섯 단계로 나누어 해당하는 단계를 선택하도록 하였다.

자료 분석

Primary outcome은 PSQI 총점의 평균변화율로 하였고, 이는 {(중재 후 총점-중재 전 총점)÷중재 전 총점}×100으로 계산하였다. 그리고 나머지 평가 항목들을 secondary outcome으로 삼았으며 같은 방법으로 산출하였다.

평가 결과에 대해서는 아래의 통계법을 사용하여 각 집단 간 유의성 검정을 시행하였고, 자료의 정규성 검정 결과에 따라 적절한 통계법을 선택하였다. 1) 조명기기 중재 전 초기 평가 결과의 실험군과 대조군 사이의 비교는 independent t-test 또는 Mann-Whitney U test로 분석하였다. 2) 각 집단별 조명기기 중재 전후 평가 결과 변화에 대한 비교는 paired t-test 또는 Wilcoxon signed rank test로 분석하였다. 3) 조명기기 중재 전후 평가 결과 변화 정도에 대한 실험군과 대조군 사이의 비교는 independent t-test 또는 Mann-Whitney U test로 분석하였다. 4) 각 평가 항목별 정상과 비정상을 구분하는 값을 기준으로, 조명기기 중재 전 비정상값을 보였다가 중재 후 정상값을 보이게 된 대상자 비율(정상화율)의 실험군과 대조군 사이의 비교는 chi-squared test 또는 Fisher’s exact test로 분석하였다. 통계분석에는 SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA)을 이용하였고, p값이 0.05 미만일 경우 통계적으로 유의한 것으로 판단하였다.

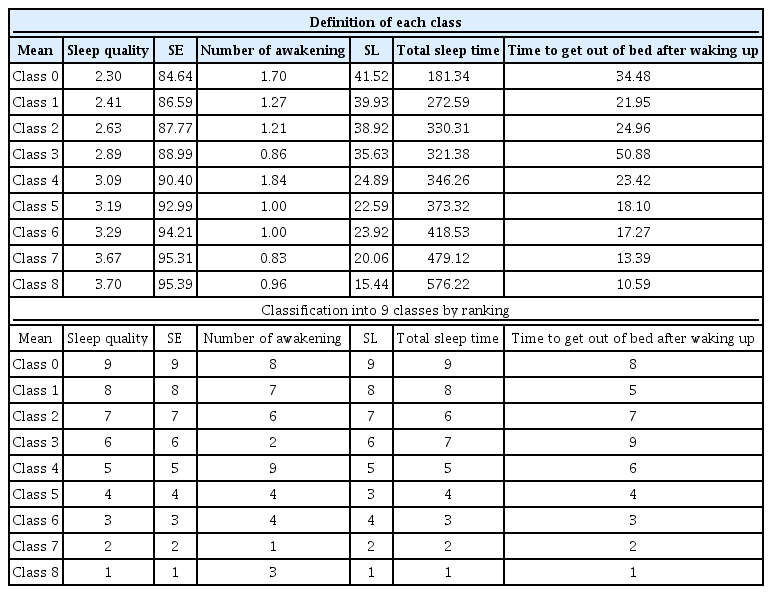

실험군과 대조군의 수면 개선 정도를 비교하기 위해 연구 참가자가 수면일기앱으로 기록한 자료 중 여섯 가지를 분석 항목으로 하여 K-평균 군집분석(K-means clustering algorithm)을 수행하였다. K-평균 군집분석은 데이터들을 유사성에 따라 서로 다른 군집으로 분류하는 방법이다. 이를 위해 무작위적으로 초기 중심값들을 선택하고 각 중심값과 개별 데이터 사이의 거리를 계산한 뒤 각 데이터를 해당 데이터와 가장 가까운 군집에 배정한다. 그러고 나서 군집마다 더 이상의 변화가 나타나지 않을 때까지 중심값 계산을 반복하여 최종 중심값을 설정한 후 각 데이터를 그 데이터의 최근방 군집에 배치하는 방법이다. 32-35 분석에 활용한 여섯 가지 항목은 다음과 같다: 1) 주관적 수면의 질(sleep quality), 2) 수면효율(SE), 3) 수면 중 각성 횟수(Number of awakening), 4) 수면잠복기(SL), 5) 총 수면시간(total sleep time), 6) 잠에서 깬 후 침대에서 벗어나기까지 소요시간(time to get out of bed after waking up) (Table 3). 이들을 수면 개선 정도에 따라 아홉 가지 등급으로 분류한 다음(Table 3) 참가자들의 데이터를 대입하여 두 집단의 수면 개선 정도를 비교하였다.

결 과

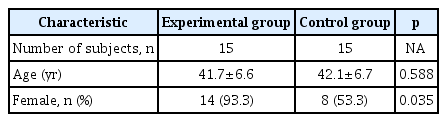

연구를 위해 자원한 인원 30명을 각기 15명씩 실험군과 대조군으로 무작위 배정하였으며, 연구 대상자 모두 실험 과정을 완료하여 결과 분석에 이용되었다. 실험군에 배정된 대상자 15명(여자 14명, 남자 1명, 평균 연령 41.7±6.6세)과 대조군에 배정된 대상자 15명(여자 8명, 남자 7명, 평균 연령 42.1±6.7세) 사이의 평균 연령에 유의한 차이는 없었으나(p=0.588, Mann Whitney U test), 실험군에 여자가 더 많이 포함되어 있었다(p=0.035, Fisher’s exact test) (Table 4). 조명기기 사용 전, 수면의 질을 나타내는 각 평가 항목의 결과값에서 실험군과 대조군 사이에 유의한 차이는 없었다(Table 5).

Values of each evaluation item before lighting intervention in the experimental and the control group

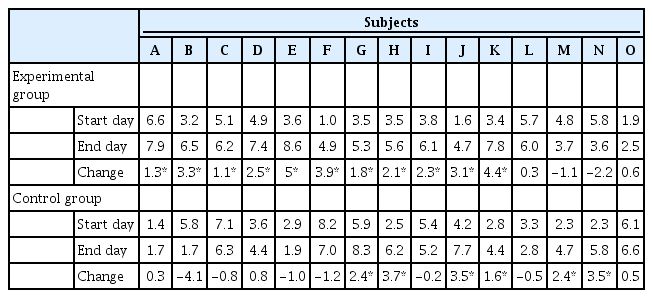

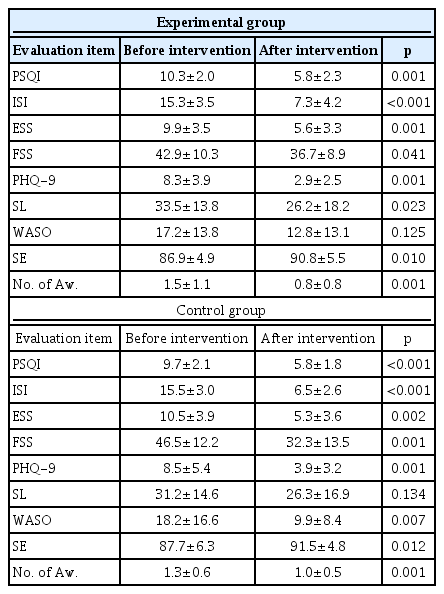

실험군에서, 조명기기 사용 전후로 설문지로 평가한 다섯 가지 수면 관련 지표들은 모두 조명기기 사용 후 사용 전에 비해 유의하게 호전되어 수면 개선 효과를 보여주었다. 수면일기로 확인한 수면 관련 지표는 네 항목 중 세 항목에서 유의하게 호전되어 수면 개선 효과를 보여주었다. 그러나 WASO값은 조명기기 사용 후 호전되는 경향은 보였으나 유의성은 없었다(Table 6).

Values of each evaluation item before and after lighting intervention in the experimental and control group

대조군에서, 설문평가로 확인한 다섯 가지 수면 관련 지표들 또한 기기 사용 후, 기기 사용 전에 비해 모두 유의하게 호전되어 수면 개선 효과를 보여주었다. 수면일기로 확인한 수면 관련 지표 네 가지 중 세 가지에서 유의하게 호전되어 수면 개선 효과를 보여주었다. 그러나 SL값은 조명기기 사용 후 개선되는 경향은 보였으나 통계적 유의성은 없었다(Table 6).

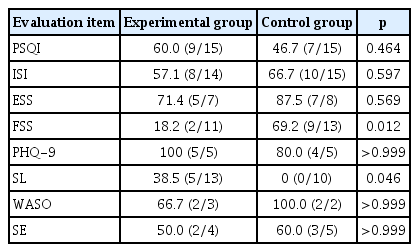

수면의 질 개선에 대한 실험군과 대조군 사이의 비교분석 결과는 다음과 같았다. 조명기기 사용 전후에 설문평가로 확인한 다섯 가지 수면 관련 항목들의 점수 변화량 평균값은 실험군과 대조군 사이에 유의한 차이를 보이지 않았다. 수면일기로 확인한 네 가지 항목들 중에서도 Number of awakening 값에서만 두 집단 사이에 유의한 차이가 확인되었으며, 그 외 항목에서는 유의한 차이를 보이지 않았다(Table 7). 각 평가 항목별 평균 개선율도 두 집단 사이에 유의한 차이는 없었다(Table 7). 한편 각 평가 항목에서 절단값을 기준으로 정상과 비정상 범주를 나눈 분석에서, 조명기기 사용 전에는 비정상 값을 보였으나 사용 후 정상 범위에 속하는 값을 보인 대상자들의 비율(정상화율)도 PSQI, ISI, ESS, PHQ-9, WASO, SE 등 대부분의 항목에서 실험군과 대조군 사이에 유의한 차이는 확인되지 않았다. 그러나 FSS값은 대조군에서, SL값은 실험군에서 정상화율이 유의하게 더 높은 것으로 나타났다(Table 8).

Change and change rate (%) of values of each evaluation item between pre- and post-lighting intervention in the experimental and the control group

Proportion (%) of subjects who showed change from abnormal values before lighting intervention to normal values after lighting intervention for each evaluation item

K-평균 군집분석을 통해 대상자 개개인의 수면 개선 여부를 분석한 결과는 다음과 같았다. 수면 등급표(Table 3)에서 중재 시작일 대비 중재 종료일의 수면 등급이 1개 등급 이상 상승한 경우를 수면 개선이 이뤄진 것으로 간주하였을 때, 실험군에서는 15명 중 11명에서(73%), 대조군에서는 15명 중 6명에서(40%) 수면이 개선된 것으로 나타났으나 통계적으로 유의한 차이는 없었다(p=0.065, Chi squared test) (Table 9).

고 찰

본 연구에서는, 아침에 청색광 비율이 높은 빛을, 밤에는 낮은 빛을 쬐는 것이 수면의 질 개선에 어떤 영향을 미치는지 알아보기 위해, 수면의 질 저하를 호소한 일반인 30명을 대상으로 실험을 수행하였다. 조명기기를 사용하여 2주 동안 아침 기상 후 실험군은 480 nm, 대조군은 450 nm 청색광이 강화된 빛을 30분 동안 쬐고, 야간 취침 전 실험군은 480 nm, 대조군은 450 nm 청색광이 억제된 빛을 30분 동안 쬔 다음 조명기기 사용 전후로 수면설문 점수 및 수면일기 기록의 변화 양상을 분석하여 수면의 질 변화를 종합적으로 평가하였다. 그 결과 실험군과 대조군 모두 전반적 수면의 질, 불면중증도, 주간졸림증, 피로중증도, 우울감, 수면효율, 수면 중 각성 횟수에서 유의한 개선이 확인되었고, 개선 수준에 있어서는 두 집단 사이에 의미있는 차이는 없었다.

청색광에 노출된 시점이 아침이라면 수면위상이 앞당겨지고 수면잠복기가 짧아지는데, 이는 아침에 청색광을 쬐어주는 것은 수면의 질을 개선하는 데 도움이 될 수 있음을 시사한다. 17 반면에 밤에 청색광에 노출되면 수면잠복기가 길어지고 일주기리듬이 지연되므로, 이는 야간 청색광 노출은 피하는 것이 수면의 질 개선에 도움될 수 있음을 시사한다[18-21].

이러한 보고들을 바탕으로 아침 기상 후, 또는 야간 취침 전 빛 중재를 함으로써 청색광이 수면의 질에 미치는 영향을 분석하는 다수의 연구가 수행되었다. 이 연구들은 빛 중재 후 수면의 질과 관련된 다양한 항목들을 평가하였는데, 대부분 한두 가지의 소수 항목에서만 유의한 개선을 보인 것으로 보고하였다.

예를 들면, 아침에만 청색광을 조사한 연구에서는 여러 평가 항목 중 WASO만, 혹은 ESS와 Beck Depression Inventory(BDI)만 유의하게 호전된다고 보고하였다[15,16]. 야간에 청색광 노출을 차단한 연구에서는 여러 평가 항목 중 SL만, 혹은 SL과 Number of awakening만 유의하게 개선되거나, 평가한 항목 중 개선된 것이 없다고 보고하였다[36-38]. 그리고 취침 전 빛 발산 전자기기를 사용한 경우 FSS가 유의하게 더 높았다는 보고도 있다[39].

본 연구에서 실험군과 대조군 모두 조명기기 사용 전에는 PSQI, ISI, ESS, FSS 점수가 비정상 범위에 있었으나 기기 사용 후에는 모두 정상 범위로 호전되었다. PHQ-9는 조명기기 사용 전부터 정상 범위의 값을 보였지만 기기 사용 후에는 점수가 더 크게 개선되었다. SE와 WASO도 조명기기 사용 전 이미 정상 범위에 있었으나 사용 후 더 크게 호전되었다. Number of awakening의 경우 정상 범위의 절단값은 설정하지 않았고, 각성 횟수가 적을수록 수면의 질이 향상된 것으로 간주하였는데, 실험군과 대조군 모두 조명기기 사용 전에는 수면 중 1회 이상 잠에서 깬 것으로 확인됐으나 조명기기 사용 후에는 잠에서 깬 횟수의 평균값이 유의하게 감소하였다. 그러나 잠에서 깬 횟수의 평균 감소 정도가 1회 미만이었기 때문에 임상적으로 의미를 부여하기는 어려웠다. SL은 조명기기 사용 전, 두 집단 모두에서 30분이 넘는 값을 보였으나 조명기기 사용 후에는 20분대로 감소하였다. 비록 본 연구에서 정상 범위의 절단값으로 설정한 시간 범위(20분 이하) 내로 호전되지는 못 하였지만, 실험군에서는 대조군과 달리 수면잠복기가 유의하게 감소함으로써 의미를 부여할 수 있었다. 실제로 대조군에서 조명기기 사용 전 비정상 수준의 SL값을 보였던 대상자들(15명 중 10명)은 조명기기 사용 후에도 여전히 비정상 범위의 값을 보였다. 그러나 실험군에서 조명기기 사용 전 비정상 SL값을 보였던 대상자들(15명 중 13명) 중 5명은 조명기기 사용 후 정상 수준으로 SL값이 호전되어 40% 수준의 정상화율을 보여주었다. 이는 실험군에서 사용한 480 nm의 빛이 대조군에서 사용한 450 nm의 빛보다 수면 잠복기 개선에 효과가 있을 것임을 시사한다. 설문평가로 확인한 다섯 가지 항목에서의 호전 변화는 수면일기 기록으로 확인된 수면 패턴 개선에 따른 결과로 생각된다. 수면잠복기가 감소하고 수면 시작 후 각성 시간이 줄어들면서 수면효율이 자연히 늘어나 대상자 스스로도 수면의 질 개선을 느꼈을 것으로 보이며, 이러한 수면 개선은 우울감 감소와도 연관될 것이라고 생각된다. 즉 불면증 개념으로 생각해보면, 수면개시불면과 수면유지불면이 모두 개선되어 수면의 질이 향상되고 우울감도 호전된 것으로 해석할 수 있겠다. 이러한 연구 결과는 아침과 밤에 복합적으로 조명 중재를 하는 것이 수면의 질 개선에 효과적일 것이라는 점을 시사한다.

대부분의 수면의 질 평가 항목(PSQI, ISI, ESS, FSS, PHQ-9, SE, and Number of awakening)에서 실험군과 대조군 사이에 유의한 차이가 없었던 이유는, 두 집단이 공통적으로 파장은 약간 다르지만 아침에는 청색광 영역의 빛을 발산하고 야간에는 청색광 영역의 빛을 제한하는 조명기기로 중재를 받았기 때문이라고 생각된다. 즉 아침에 조사되는 빛은, 실험군에서는 480 nm, 대조군에서는 450 nm 영역의 빛이 극대화된 것으로서, 파장이 400-500 nm 영역인 빛이 청색광인 것을 감안하면 두 집단 모두 청색광을 조사받은 것이었다[40]. 이러한 결과는 청색광 파장대의 빛이라면, 세부 파장에 약간의 차이가 있더라도 수면의 질을 개선하는 효과에는 큰 차이가 없을 가능성을 시사한다. 다만 수면잠복기는 실험군에서만 중재 전후로 유의하게 개선되었기 때문에, 청색광 영역 내 빛의 파장 차이는 수면잠복기 변화에 영향을 줄 수 있으며, 480 nm 파장의 청색광은 수면잠복기의 유의한 개선과 관련이 있을 것으로 생각된다.

본 연구에서는 조명기기 사용 효과를 평가하기 위해 중재 전후로 각 평가 항목별 평균값을 비교함으로써 수면에 미치는 영향을 분석하였다. 그러나 이는 대상자 개인의 변화 양상을 종합적으로 판단하기는 어려워 K-평균 군집분석 방법을 추가적으로 활용해 이를 파악하고자 했다. 그 결과 비록 통계적 유의성은 없었으나 실험군에서 수면 개선이 이루어진 대상자들의 비율이 대조군에 비해 더 높은 경향을 보여, 각 개인별 조명기기 사용 전후 평가 항목의 변화 양상으로 수면 개선 효과를 판정하는 것이 조명기기 사용 효과를 좀더 민감하게 평가하는 방법일 수 있음을 시사하였다.

본 연구에서 대조군의 조명도 실험군에 비해 파장 영역에서의 작은 차이만 있었을 뿐, 청색광을 포함하고 있었기 때문에 청색광이 수면의 질에 미치는 영향을 평가하기는 다소 어려웠다. 그리고 조명기기 사용 전 시행한 설문평가에서 참여한 대상자들 대부분이 경미한 수면장애만을 보였기 때문에, 빛 중재에 따른 수면의 질 개선 효과가 뚜렷하게 드러나지 않았을 가능성이 있다. 또 실험군에 여자가 편중되어 있어 성별에 따른 차이도 고려해야 한다. 향후 중증 수면장애 환자를 대상으로, 청색광을 좀더 다양한 파장대로 세분한 뒤 파장대 별로 아침 또는 야간에만 중재한 군과 두 시점 모두에 중재한 군으로 분류하고, 이에 대응되는 대조군에는 청색광이 완전히 배제된 빛을 발산하는 기기를 사용하여 수면 개선 효과를 비교한다면 주야간 복합 중재의 효과와 파장대별 청색광이 수면에 미치는 영향을 종합적으로 평가할 수 있을 것으로 생각된다. 본 연구를 통하여 아침에는 청색광이 강화된 빛을, 야간에는 억제된 빛을 함께 중재하는 것은 수면의 질을 개선하는 데 효과적이며, 그 효과의 크기는 사용한 청색광의 세부 파장 차이에는 큰 영향을 받지 않는다는 것을 알 수 있었다.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.13078/jsm.230016.

A sleep diary application input screen.

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Ki-Young Jung. Data curation: Wankiun Lee. Formal analysis: Wankiun Lee. Funding acquisition: Ki-Young Jung. Investigation: Wankiun Lee, Ki-Young Jung. Methodology: Wankiun Lee, Ki-Young Jung. Project administration: Wankiun Lee, Ki-Young Jung. Supervision: Ki-Young Jung. Visualization: Wankiun Lee. Writing—original draft: Wankiun Lee. Writing—review & editing: Wankiun Lee, Ki-Young Jung.

Funding Statement

This research received grants from LUPLE, Inc. in Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022.